22nd August 2025

This September, FCN is championing all things forensic research. The network aims to bring cutting-edge academic innovation into operational policing, starting with an exciting week-long Research Festival on 6-10 Sept. FCN also coordinates R&D investment, encourages innovation and shares knowledge across the community. Find out more about our six vibrant research groups or read our in-depth interview with Professor Simona Francese at Sheffield Hallam University on her molecular fingerprinting research.

Bringing you the latest academic research which can be applied in policing, our first ‘research round-up’ includes…

Dr Steve Bleay, Senior Lecturer in Forensic Science, London South Bank University. Join Dr Bleay’s presentation at the FCN Research Festival in 6-10 Sept. Register here.

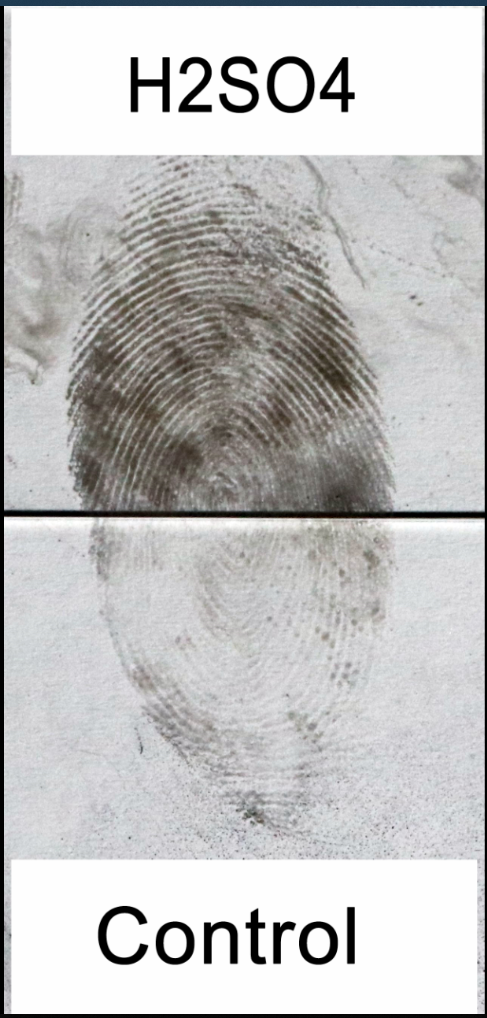

An internally funded feasibility study conducted at London South Bank University has been exploring whether it is possible to recover finger-mark evidence from surfaces that may have been exposed to corrosive substances.

The objective is to establish if evidence could survive on the types of containers (typically polyethylene terephthalate, or glass) used in corrosive substances attacks, and if so, which processes would be most effective in visualising marks.

The study has used one acid (sulfuric acid) and one alkali (potassium hydroxide) at concentrations up to 4M, and it has been shown that finger-marks can survive exposure to both environments provided an appropriate visualisation process is used. The alkali environment appears more detrimental, but finger-mark recovery is still possible. The results are currently being written up as a journal paper submission.

Martin Hall, Scientific Associate at Natural History Museum London

Forensic entomology is the use of insect evidence to assist legal investigations. A special free issue of the journal Insects was recently published on the challenges faced in moving from laboratory studies of forensic entomology to court evidence.

The journal features a paper from Martin Hall on the relationship between research and casework, written from his 30+ years’ involvement in more than 200 cases within the criminal justice system of England and Wales.

The paper shows how questions raised in casework can be addressed by research to feed back into future casework. A technical note by Senta Niederegger neatly illustrates the value of this mutually beneficial, circular relationship, showing how vodka and brandy can be used at a scene if the more standard insect preservatives are unavailable!

Most forensic entomology research is aimed at improving estimates of the time of insect colonization of victims of unexpected death, which can inform estimates of their time of death—Szymon Matuszewski reviews the current challenges in producing such estimates. This special issue demonstrates what an exciting and dynamic time it is to be working in applied forensic entomology.

Dr Noemi Procopio, Principal Investigator of the “Forens-OMICS” team at Northumbria University. Follow Dr Procopio and @ForensOMICS on Twitter.

A new research team led by Northumbria University’s Dr Noemi Procopio and supported by the prestigious UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship is applying “omics” technologies—such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and lipidomics—to human forensic bones in order to develop new methods to estimate chronological age and PMI in a measurable, objective and reliable way.

So far, they have collected more than 120 human bone samples from three different forensic anthropological facilities, also known as ‘body farms’, in the USA (FAC at the University of Tennessee, FACTS at Texas State University and STAFS at Sam Houston State University) and started to extract biomolecules from them such as DNA, proteins, metabolites and lipids. The age of the selected donors ranges between 18 and 107 years, and the postmortem interval (PMI) from 35 years to a few months.

Dr Procopio says:

“We aim at developing ‘single-omics’ and ‘multi-omics’ models by using machine learning approaches in order to evaluate how biomolecules can accurately predict age and PMI starting from minimal amounts of bone powder. The ultimate goal will be the development of easy-to-use analytical kits for ageing estimations that could be employed also by non-omics experts including police forces and forensic scientists.”

Besides the main research, she is conducting additional studies on other topics in collaboration with several international colleagues. Among them is investigating the use of the microbiome for personal identification and for PMI estimation.

She adds:

“For the first application, we are currently analysing samples taken from living donors from different countries to identify microbes associated with specific lifestyles, geographical proveniences, health status, etc that could provide intelligence information to open new investigative leads.”

For PMI estimation, the team has recently set-up an experimental mass grave at FACTS in Texas where six donated cadavers will decompose for a period of 18 months. At regular time intervals gravesoil in contact with the bodies will be sampled, allowing them to test if the current understanding on the microbial shifts associated with specific PMIs can be applied to mass grave contexts as well as to single burials.